St. Thomas’

Church, Whitemarsh

Advent 3, Year C,

2015

You brood of

vipers!!

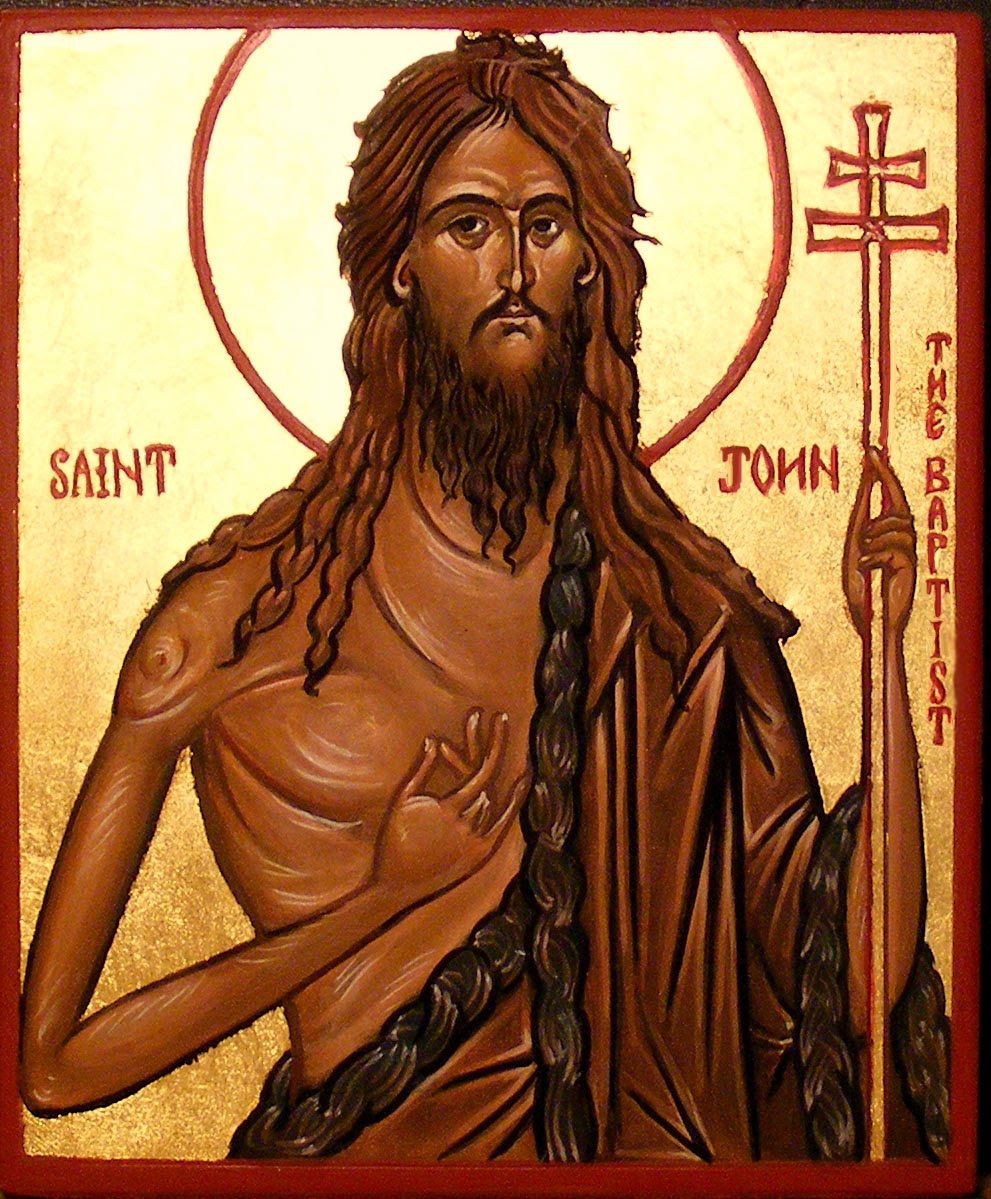

John the Baptist:

that wild, locust-eating, camel-clothed cousin of Jesus; he never could keep

his mouth shut, could he? To be fair, my imagination probably unfairly

caricatures his ranting and raving. I’m sure that he was less like a yelling

caveman from the GEICO commercial and more like an Elijah or MLK, Jr. figure, a

dynamic, passionate, earnest speaker who had a vision of what a righteous life

was supposed to look like and called people out when they strayed from the

path.

In Matthew and

John’s gospels, the brood of vipers is referring to the Pharisees and priests,

the elite religious leaders of the Jews. John was calling them out for taking

advantage of their faithful people, of placing more emphasis on following the

letter of the law than actually taking care of the people they served.

But today we hear

from the Gospel according to Luke, who emphasizes God’s love for the poor, the

downtrodden, the outcast. And in Luke’s version, the people who get called a

brood of vipers are not religious leaders who have come just to spy on John or to

see a spectacle, but people who have traveled to the wilderness to be baptized

by John. Not exactly the way to win the hearts of the people who want to follow

you—or so you would think. But John doesn’t want fair-weather followers. He

tells them straight up that if they really want to prepare for what is coming

they can’t just get baptized and then sit back on their haunches,

self-satisfied. It is not enough to say they are children of Abraham, God’s

chosen people; they need to show their contrition by bearing “fruits worthy of

repentance” (Luke 3:8). If they are truly repentant, they will have had a change of

heart and their actions from that time forward will demonstrate this change of

heart. This means no more taking advantage of one another! The tax collectors

can’t take extra money on top of what they are required to collect, and the

soldiers can’t bribe or falsely accuse people to get more money, but should be

content with the wages they earn (vv. 12-14). These actions seem to be simple,

obvious things: don’t contribute to making the poor poor, but help out the

people disadvantaged by the system, the same system that allows you to take

more than you need.

The tax

collectors and soldiers—the ones with some power over their fellow Jews—were

not the only ones called out. The crowd asked John how they could prepare

themselves, and he told them to share their coats and food with those who don’t

have any (vv. 10-11). Even if you are not wealthy compared to those in the

upper classes, you are still able to help others out.

To all of these

“exhortations” the people didn’t leave dejected but responded by being “filled

with expectation” (vv. 18, 15). They wondered if John might be the Messiah, the

one they believed would overthrow the oppressive Romans and bring about the

reign of God. But John told them that they were waiting for someone greater,

someone for whom he was not even good enough to be a slave (vv. 15-16).

So what message

is John telling us today? We have the advantage of knowing how the story of John

and Jesus not only begins but ends. Soon after this passage, John is arrested,

effectively ending his ministry, and Jesus is baptized, marking the beginning

of his ministry. In his teachings, the thing that Jesus emphasized more than

anything else was to love God and love our neighbor. It’s simple enough on

paper but difficult to actually put into action.

Like the warning John

gave the Jews he was preaching to, we too must be careful not to become

complacent. If we call ourselves Christians but then ignore the needs of our

neighbors—not just our literal neighbors but all children of God—then our behavior does not reflect one of true Christianity.

Judith Jones,

professor of religion at Wartburg College, asserts that “Economic issues are spiritual

issues. If we ignore God’s commands to practice social and economic justice,

how can we claim that we love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength?

If we prioritize our pleasures above our neighbors’ basic necessities, how can

we claim to love our neighbors as we love ourselves?”

At our baptism,

we—or people on our behalf—made promises to follow Jesus Christ, to “seek and

serve Christ in all persons, loving our neighbors as [ourselves],” to “strive

for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human

being” (BCP 303, 305). This means that we cannot sit idly by as our sisters and

brothers suffer; everyone is called to contribute what they can to bring about

the kingdom.

We also promise

that when—not if, but when—we fall short, we will “repent and return to the

Lord” (BCP 304). Yes, we are made in the image of God, and reborn in the waters

of baptism, but we are hardly perfect.

When

John talks about Jesus coming to baptize people with the Holy Spirit and fire

and to separate the wheat from the chaff, it’s easy to assume he means

separating people according to their goodness. But as Harry

Potter author J.K. Rowling writes in book five of the series, “the world isn't split

into good people and [bad].

We've all got both light and dark inside us.

What matters is the part we choose to act on. That's who we really are.”

What

John is trying to convey is that in the same way that we occasionally have controlled

burns of forests to allow for new growth, when Jesus comes, the parts of us

that separate us from God will be burned away. All of our prejudices, anxiety,

perfectionism, anger, regret—it will all be removed so that we can finally love

God with all our heart, mind, and soul, and our neighbors as ourselves. This is

Good News!

In this Advent season

we cannot simply stand still. Like the crowd in front of John, we are called to

bear fruits. We do this by remembering the vows we made at our baptism: to take

care of one another, demonstrating God’s love to those around us, both stranger

and friend, until the day when Jesus returns once again.

(image found here)